Does zooming in help us zoom out?

The power of the 'micro-notice' to unleash creativity, as tested in a photo-walk and poem.

The ‘micro-notice’

We are used, as writers, to relishing the finer details, the tiny things that we see and others overlook. We are often told how this will help make our descriptions pop and feel more realistic.

I remember one of my early writer friends describing this as the notice. What is your personal observation, your unique take? What do you notice, what it does it say about the setting or the character, and how does it drive the narrative forwards?

Noticing something is often to do with zooming in. One of my favourite writers, Jim Crace (Harvest, Eden, Quarantine…) is known for his forensic detail. He specialises not just in ‘notices’ but what I’d call the ‘micro-notice.’

I remember in particular the microscopic accounts of decaying flesh and matter in his Being Dead: the colonisation of bacteria on the skin and fat, the tissue as it liquifies and mulches, the attrition of sea-salt on bone, the gases that bubble and burst and their molecules of sweet stink.

The book starts with two corpses, and with each chapter the parade of parasites that attend them gets smaller and smaller, creating a marching order from foxes down to barely visible fungi. As he zooms in to details of decay we’d normally never consider, he gets us thinking more widely about the ravages of death, our impermanence and the mundane materiality of our bodies.

He zooms in, we zoom out.

Being Dead runs with this metaphor of decay and applies it to decomposing relationships, emotions and memories. It is a beautiful and bittersweet read. And it also is typical of Crace’s writing approach, a fine example of how by going into minute, sometimes scientific detail, you can enrich your metaphors and symbols.

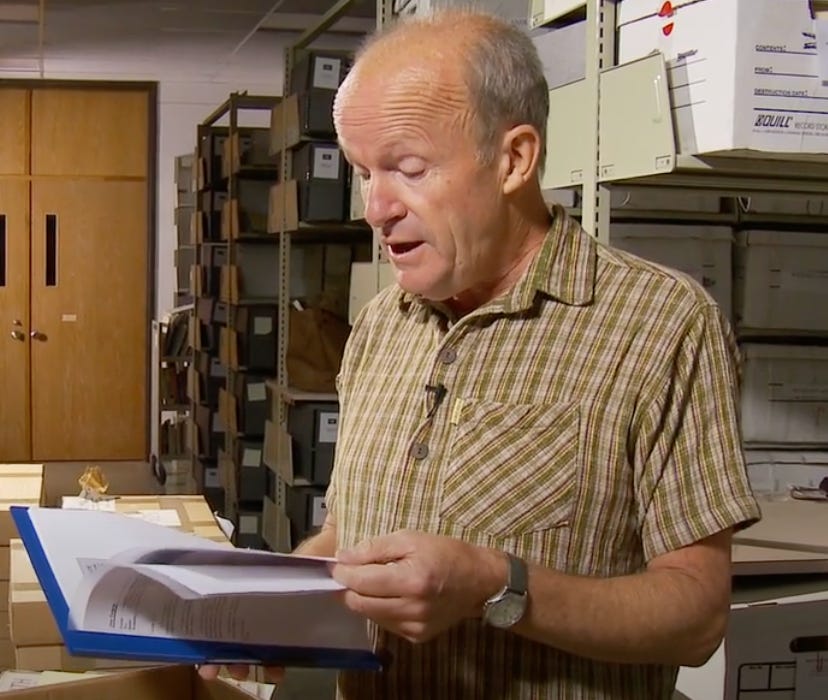

Such notices and micro-notices can also substitute for emotional language. In this short video, Crace shares how an ‘objective’, detailed description can invite a keener subjective response in the reader than a gushing description of a character’s emotions. So, a description of a coffin — its tarnished brass handles, the gloss of the black paint, the flowers that have slipped — is enough for us to respond with our own sentiment, our own recollection of grief. We don’t need to be told how very, very sad the character is. He puts it this way:

‘Be specific with the thing and reticent with the emotion.’

What’s happening?

The devil’s in the detail. We are indeed back to that truism. And God’s in the detail, too. Think of Blake’s poem on how divine creation is reflected in the smallest of things:

To see a world in a grain of sand

And heaven in a wild flower,

Hold infinity in the palm of your hand

And eternity in an hour.

(from Auguries of Innocence)

It got me thinking about how this micro-to-macro relationship works. Could it be that the closer we zoom in, the more abstract our view of the object becomes and therefore the more potential there is to free-associate, accessing the peripheries of our imagination? And does this mining of the peripheries yield a more original and evocative metaphor?

Is describing a small blade of sunlight and its illumination of the veins of a petal more evocative than painting a big canvas sunset?

I suppose it depends on how skilfully we do either, of course. One description can be as hackneyed as the other if we’re not careful. You might think my sunlight-through-petal-veins is clichéd, for example.

This is all too easy to talk about theoretically, so I decided to go on a photo-walk to put the concept to the test. What if I wanted to write a poem based on summer turning into autumn and that liminal state between the seasons?

Giving it a go

When I do my early morning loop of the park, my gaze normally falls loosely over the whole scene, the macro. I might take in the sweep of the grass down to the pond:

Or appreciate the clouds and the general invitation of the sky to think big:

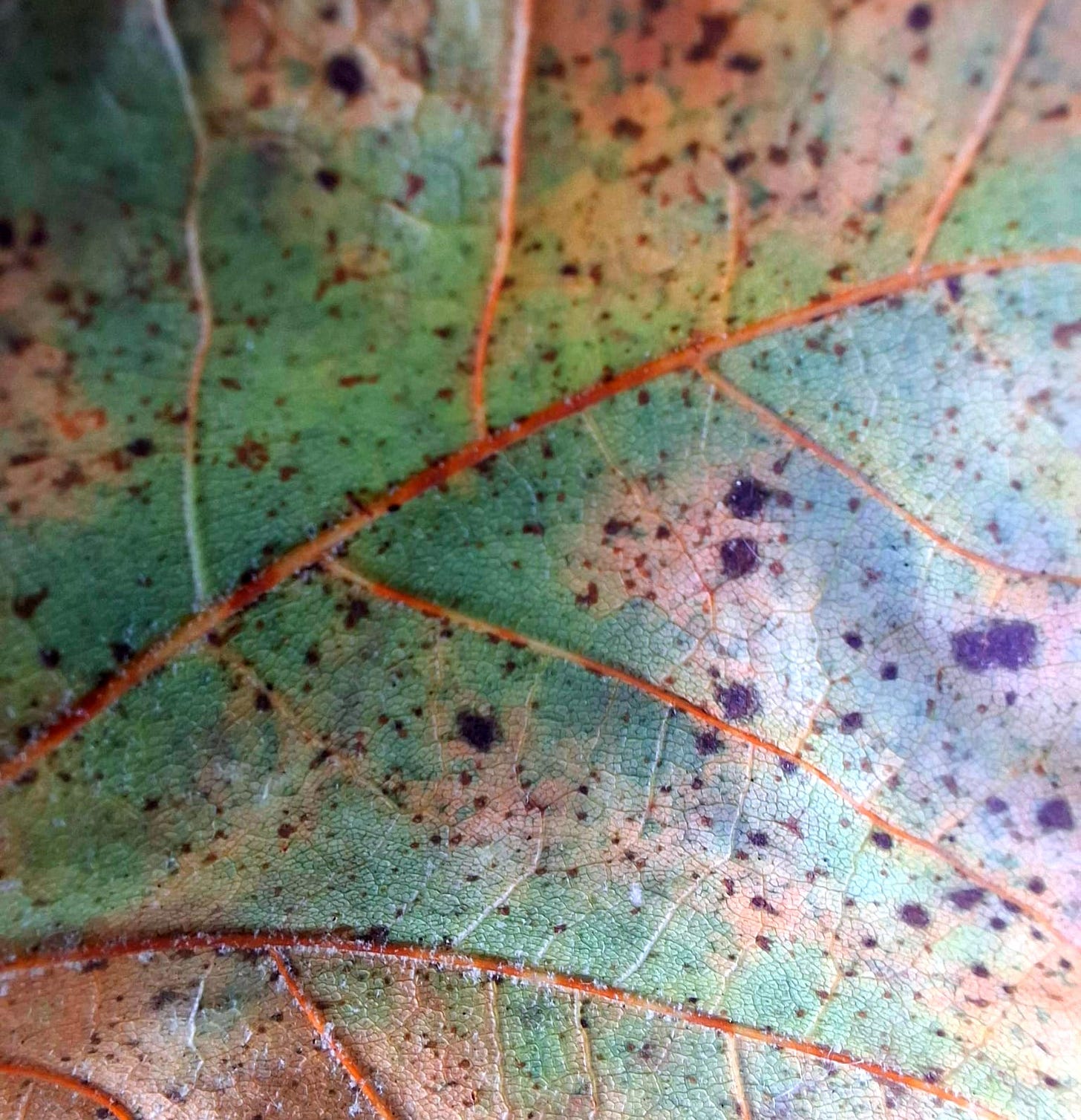

This morning, though, I set my phone’s camera to ‘macro’ and began kneeling into the grass to spot something photogenic, like patterns on pre-autumnal leaves:

The first, on the left, makes me think of mottling, freckling, of liver spots and ageing. The second bears a light scorch mark, a singeing as if being licked by a match flame beneath. The third is a leak of bleach from the centre, or a re-pigmentation, a vitiligo of sorts.

Good. Already getting some more poetic images than my usual autumnal tropes. I carried on, this time spotting some feathers among the detritus:

The first looks freshly hatched, a mixture of delicate barbs and down, their gentleness almost a promise of life in the bed of decaying leaves. In the second I was drawn to the batch number on the empty Biscoff packet, its strange specificity next to a commonplace, anonymous feather, its incongruous red and vibrance among all the dead browns. Is this grubby little wrapper a leaf in its own way, shed and left to curl unseen?

A poem about shifting into autumn

Here is my attempt at riffing off some of those images in a short poem:

Summer is sickening.

The barbecues sputtering out,

the parties greying with the day,

the balls grounded from flight,

and the dogs curiously quiet.

The grass smells blank and

the lake, rain-starved, stinks

of crowded duck and mould.

The leaves, now fevered and

stricken by yellow-rash,

begin their burn and curl,

falling from seen to unseen,

browning among other things shed:

the feather, the biscuit wrapper

with its grubby red,

the damp fags left for dead.

I took twenty minutes on that, trying to work from the macro to the micro. I’m not sure I got there, and could have gone deeper. I think Crace would have described the fetid mould and the patterns of the leaf rash in scintillating detail. Still, it’s a start.

Micro-notices across the senses

So far, I’ve kept the focus on visual elements. What would pass as micro-notices in the rest of the senses? Here are some thoughts:

Instead of smelling vanilla, how about clotted cream and crushed pods?

Instead of a forced gait, the twist in the arch of a foot.

Instead of a beautiful chord, the pent-up tension of an interval that won’t resolve.

Instead of birdsong, the rough edges of a chirrup and how it abrades the silence.

Instead of the smooth gloss of a pot, the braille of dimples in the clay.

You get the drift. Happy zooming!