Combinational thinking

Why take one seed idea when you could take two? Your creative exercise for the week.

Red.

What comes to mind from that one word, what images flow from it? Spend a moment just free-associating, see what crops up.

Now try ‘rust red’.

Immediately the thought-life gets richer, doesn’t it? Why the rust and why is it red? We have the beginnings of a story.

Creative cognition is all about combinatory thinking, even if it’s just smooshing together two words. We take an old thought and combine it with a new one, and that’s where creativity kicks in. We go from ‘monkey’ to ‘ravenous monkey’, or ‘towel on a chair’ to ‘wet towel dripping on a chair in a desert’.

Learning and creativity have a lot in common in this respect, to the point of being coterminous. When we learn we are being creative, and when we create we are learning. They occupy the same patterns of cognition, and are both examples of constructivism, or binding new knowledge onto old. In some taxonomies, ‘creating’ is even named as the ultimate stage of learning. If you can create, that demonstrates you have assimilated the knowledge to the degree where you can turn it to your own ends.

Perhaps with creativity there is more emphasis on the end-product being imaginative and off-piste, containing an element of surprise. You could represent it as:

Learning: 2 + 2 = 4

Creativity: 2 + 2 = tutu

How do we exploit this constructivist pattern as creatives? How do we deliberately set our minds into creative motion through combining concepts and practices, learning as we go? I thought that, in the spirit of this Substack, I’d give it a go.

Elgar, an Abbot and clouds

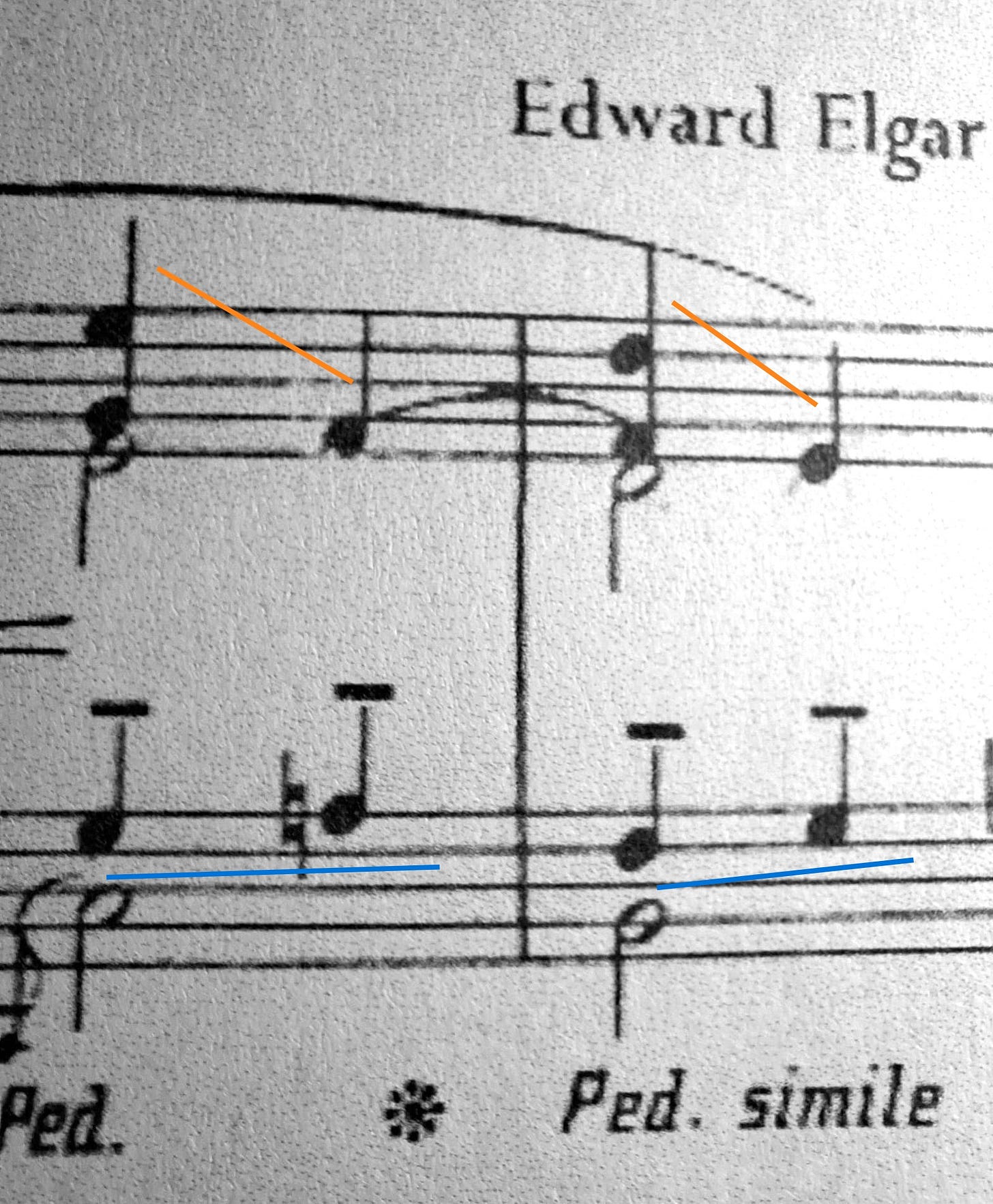

I was improvising on the piano recently, taking this piece by Elgar as my starting point. Recognise it?

It’s ‘Nimrod’ from his Enigma Variations. The variation that gets rolled out on national occasions where audiences are invited to puff their chests and feel a swell of pride in the imagined glories of the past.

For my improvisation, I could just riff off the falling sevenths in the right hand (shown with orange lines). That would be decent enough. However, what makes this more interesting is combining those falling gestures with the rising couplets in the middle line (in blue) of the left hand.

Now, I feel, we have a story: the legato falling against the marcato rising. The ideas are in creative tension and I can play with how they move towards or against each other. They happen to be antithetical, but I could have picked a more complementary or subtle counterpoint.

All that matters is that the two or more ideas you settle on begin to chirr when brought together, that they begin to whisper something new.

(I’d record some improvisations here for you if I could, but I’m currently on holiday and without a keyboard. My fingers are going through the motions instead, paddling the air like a flipped woodlouse. Maybe I’ll add an audio file post-publication, once I’m reunited with my trusty Blüthner.)

I’m now wondering how I could transpose this basic juxtaposition of ideas, this fall-against-rise into different media. I’m reading Samantha Harvey’s marvellous book, The Western Wind at the moment, so my mind is half in medieval Somerset. The falling line brings to ear the descending cadence of an old Abbot’s speech: slightly patronising and sermonising (imagine ‘Dearly beloved brethren’, from high to low in a slow glissando). In the rising couplets I can hear the short words of a stolid, stubborn, illiterate monk, a new arrival to the medieval monastery.

So, here’s a quick dialogue combining long falling statements from the Abbot with short, upward-inflected questions from the novice monk in his charge:

Long descending statements with short rising questions:

Abbot: Brother, you are very, very new to the yoke of the Rule. Bear with it a while longer and you will soon find in it succour to the soul, I promise you that much.

Novice: Will I?

Abbot: ‘Reverend Father’, don’t forget, my son, as we are bound together in spiritual family here: you to me, and us all to our heavenly Father.

Novice: Reverend Father, will I? Get used to it?

Abbot: Many a monk will have searched their soul in their first months here, but soon the walls and cloisters become as fortresses to your resolve, mark my words. Now, Matins approaches and I have yet to find my rosary, so…

Novice: If it’s a mistake? What then?

Abbot: There are no mistakes in the will of the Good Lord, child, and you’d do well to remember that before you loose that tongue further and set it wandering on misguided errands.

Novice: Is your rosary red? With rust? On the chain?

Abbot: Whether my rosary is a fashionable Italian red or not should not concern you, my son, although I will divulge that I did in fact receive it as a delicate and timely gift from the wonderful Monsignor Farnese on his last sojourn.

Novice: I think Martha has it? The maid? In her chamber? But you’ll know where, Reverend… Father?

Ok, so I’ve played into the Corrupt Priest trope, but it was fun. I observed that it was quite hard to keep the novice speaking in questions, and was surprised to see the ‘rust red’ image return unbidden. I certainly didn’t start out with that final reveal in mind. Our minds combine ideas subconsciously, of course, and that’s part of the surprise.

Here’s a photographic interpretation of falling long lines punctuated by staccato ideas, again courtesy of Sara Blessed:

Are these ‘Mare’s Tails?’ Cirrus Uncinus? Or sinister vapour trails strewing and sputtering their chemicals against an innocent blue? Or sky jellyfish? You decide. The main thing is the clear counterpoint, the combination of ideas, the constraints observed, the story suggested: something created and something learned.

Instead of taking a seed, take a pair of seeds and see what grows out of that hybrid.

I’d love to see your response to the falling-line-rising-couplet theme, so do comment below to share some ideas:

As usual, please do take a moment to heart and restack this if you’ve enjoyed this creative prompt. Thanks!

Happy creating!